What legislation for the digitilization of life and benefit sharing ?

If free access to « digital sequence information » (DSI) of living organisms were to be unconditional, it would come up against the fair and equitable sharing of the benefits generated by the use of any physical genetic resource. Because this sharing of physical genetic resources is actually taking place within a framework of existing international texts. Despite those texts, national laws are splitting between a regulated access to data with benefit sharing on one hand and totally free access with no sharing on the other.

According to the country concerned, the Digital Sequence Information (DSI) of genome would sometimes be considered as being equal to the actual physical genetic information (as with Brazil, Columbia, Ethiopia, India…) or, at other times, as totally different (as with Australia, European Union, Japan, South Korea…). Subsequently, access to and benefits relative to the use of living organisms are subject to diametrically opposite consequences.

International laws are very variable

India, for example, claims that its law on biological diversity apply equally and unequivocally and to both physical resources and digitalized data [1] [2]. Ethiopia made the same statement : “The revised draft (…) ABS proclamation incorporates DSI in its scope of application and the definition of genetic resources. A “genetic resource “(…) includes the derivatives and their digital sequence informations”.

Quite differently, but based on the same international texts (!), other countries draw completely opposite conclusions. Thus, the European Union [3] and its member countries “consider that DSI is not the equivalent to a genetic resource (…). PIC (Prior informed consent) cannot and should not be required for access to DSI, including from publicly available databases” [4].

What do these international texts say ? Since 2016, a number of international bodies have been studying the question of DSIs with regard to benefit sharing [5]. They include the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) and the Nagoya Protocol (on Access and Benefit Sharing, ABS) ; the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture (ITPGRFA), the WHO framework for Pandemic Influenza Preparedness (PIP) ; the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) [6] [7]…

Benefit sharing is legally defined

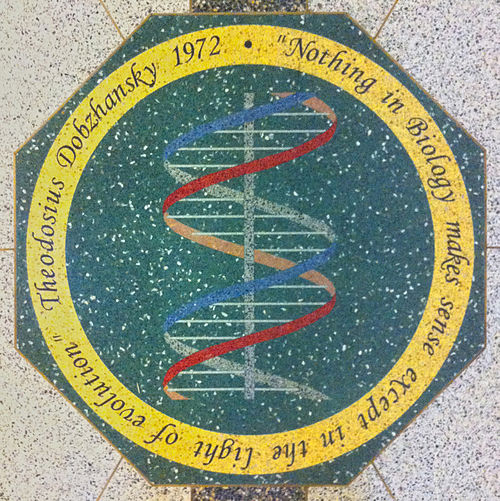

The Convention on Biological Diversity, which came into force in 1993, is “the international legal instrument for the conservation of biological diversity, the sustainable use of its components and the fair and equitable sharing of the benefits arising out of the utilization of genetic resources » [8].

There are two international texts concerning this third objective of “benefit sharing ». On one hand, there is the Nagoya Protocol (effective as from 2014), under the CBD framework, enforcing “access to genetic resources and the fair and equitable sharing of benefits arising from their utilization » [9] ; on the other hand the ITPGRFA [10] under the FAO framework (already effective in 2004).

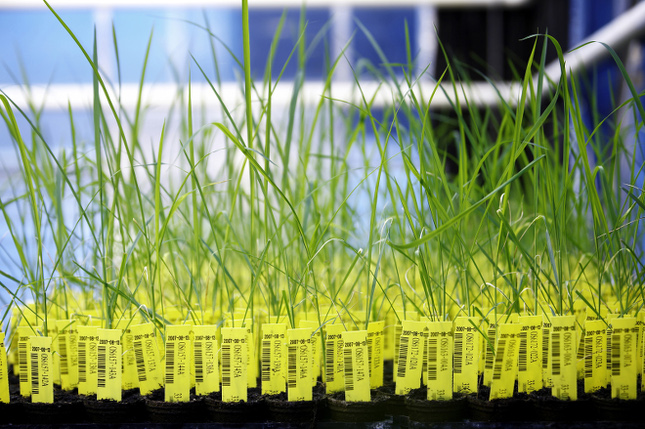

The ITPGRFA concerns 64 cultivated species [11] and their food and/or agricultural use. The Nagoya Protocol applies to all other genetic resources as well as those listed in the ITPGRFA for all non-food utilization.

The aim of these texts is to allow the access to and utilization of genetic resources, along with the payment of part of the derived benefits according to a Material Transfer Agreement (MTA) [12], signed between the user party and the sovereign state (holding the resources [13] for the CBD) and with the Treaty’s Benefit Sharing Fund, which mutualizes the distribution of the sums collected. Theoretically the advantage should be given to farmers in the developing countries but, in reality, it is given to the plant (phylogenetic) resource research organizations utilizing the resources they hold.

It is to be noted that benefit sharing may be monetary or non-monetary. Annex 1 of the Nagoya Protocol [14] puts forward a few examples : revenue sharing from rights and licensing fees, technology transfers, capacity building, access to data-bases [15]… ITPGRFA has a multilateral system of access and benefit sharing (SLM) providing resources to beneficiaries. The latter has a commitment (but rarely respected) to pay part of the sales revenue of commercialized products that have been derived from the genetic resources [16]. However, nothing obliges the patent-holders to declare whatever resources they may have used and thus to share the subsequent benefits. A farmer, on the other hand, has to buy the seeds of a given variety whose price includes a license fee, and is thus paying royalties on the seeds coming from his own harvest ! Furthermore, if the genome of a plant has been sequenced, some argue that the very fact of making the sequences generally available is also a form of benefit sharing [17].

According to the President of the French Fondation pour la Recherche sur la Biodiversité (FRB), “the exchanges relative to a fair and equitable sharing of the benefits would only concern a few thousand or tens of thousand euros on a global scale” [18]. In fact, the international texts guarantee no more than very little redistribution, and have in no way prevented cases of bio-piracy meaning the utilization of a resource with neither prior consent nor benefit sharing. Furthermore, by patenting a resource, its genes or the genetic data it contains, they forbid de facto its utilization by the original owners of the given resource (See the recent examples of the flour Eragrostis teff [19] and tisane Quassia amara [20] etc.).

Two authorities, first the ITPGRFA in 2015 and then the CBD in 2016 noted discrepancies in the status of digitalized sequences and created ad hoc groups to examine the question. The last CBD meeting took place in March 2020 [21]. And the last ITPGRFA meeting occurred in 2019 [22] and had to admit failure. The CBD signatory states also contributed to this debate [23], the aim being to find agreement on benefit sharing during the COP15 in China, which has been postponed until 2021 due to the Covid19 [24].

WHO and sharing the influenza virus

In its introductory statement, the Nagoya Protocol declares itself to be “”mindful of the international Health regulations (2005) of the World Health Organization (WHO) and the importance of ensuring access to human pathogens (…)”. Its Article 4 establishes exceptions to the benefit sharing, “where a specialized international access and benefit-sharing instrument” can be applied in conformity with the aims of the protocol. This is the case for some pathogens like the one causing influenza.

In 2011, WHO adopted a Pandemic Influenza Preparedness framework in view of the exchange of viruses and access to vaccines and other benefits, under the acronym PIP [25] [26]. A PIP review group examined the question of benefit sharing. The group deplored the fact that “genetic sequence data [27] are not included in the definition of PIP Biological Materials”. It thus took care “to ensure that it is guided by the same principles as the governing the sharing of genetic material” [28]. In April 2019, its Director General proposed, amongst other things, that WHO should explore “possible (…) global multilateral mechanisms, for pathogen access and benefit sharing (…) in harmony with the Nagoya Protocol and its principles” [29]. A complete report is to be provided for the 74th World Health Assembly in May 2121 [30].

Furthermore, WHO is drawing up a Code of Conduct for open and timely sharing of pathogen genetic sequence data during outbreaks of infectious disease [31], and is particularly keen that the data should be rapidly put online, even if no scientific article has yet been published. This online release is to be accompanied by a prior application for authorization to utilize the data [32].

Thus, on one hand, there would be benefit sharing with the populations involved, possibly in the form of vaccines ; on the other hand, there is a concern that a researcher sharing the genetic sequence of a pathogen should not be deprived of all remuneration for his work [33].

As such DSIs often lead to patent applications, it may be expected that the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) should be watchful on the issue of benefit-sharing. Although there is no doubt that, in July 2019 [34], it defined new standards for recording nucleotide and amino-acid sequences requiring declaration of the living organism from which the sequences originate, nonetheless it has not yet requested their geographical origin. Thus, benefit sharing is impossible. However, discussions are in progress by the WIPO intergovernmental commission on intellectual property on genetic resources, traditional knowledge and folklore (IGC) [35] to ensure that « patent applicants (…) disclose the source or origin of genetic resources and evidence of prior informed consent and benefit-sharing » [36] [37].

So what about France ?

In 2016, France included the Nagoya Protocol in its Law on the recovery of biodiversity, nature and landscapes [38], but has been severely criticized by the environmental section of the Economic, Social and Environmental Council (for a virtually impossible application of the benefit-sharing modalities and the non-promulgation of the prescriptions and rulings [Bilan de la loi pour la reconquête de la biodiversité, de la nature et des paysages (Report on the law on the reconquest of biodiversity, nature and the countryside) Op. Cit.]]… and this without considering “digital sequence information”. Could this be a bad omen ?