News

GMO/non-GMO equivalence: the Commission turns “certain cases” into a general rule

The proposal to deregulate some of the GMO plants made by the European Commission in July 2023 is based in particular on the assumption that new techniques of genetic modification can produce organisms with modifications that could also be obtained using so-called “conventional” methods. To make this claim, the European Commission uses a subtle but decisive semantic abuse in its proposal…

Since July 2023, the European Union has been discussing the possible deregulation of numerous GMOs. The arguments put forward by proponents of this deregulation are striking for their numerous abuses and semantic distortions. Sowing confusion and ambiguity around established concepts, these semantic abuses are used deliberately to serve a political objective aimed at deregulating a number of GMOs. After noting that the very concepts of “genetic resources“, microorganisms, and even the definition of a GMO are twisted at willi, having deciphered the confusion between tools (e.g. Crispr), techniques (e.g. mutagenesis) and methods (e.g. technical protocols for genetic modification)ii, and having examined the terms precision, targeting and control of genetic modification techniquesiii, Inf’OGM addresses one of the European Commission’s two central assumptions, namely the “equivalence” between GM plants and conventional (non-GM) plants.

“Certain cases” or all cases?

In its introductory remarks explaining the reasons behind its proposal to deregulate numerous GMOs obtained using new techniques of genetic modification (referred to by the Commission as “new genomic techniques”/NGT), the Commission argues that “In certain cases, substantially equivalent plants can be obtained with conventional breeding methods and with targeted mutagenesis and cisgenesis“. This argument is subtly transformed in the rest of the text, moving from “certain cases” to NGT in general. The Commission writes in recital 2 of the proposed legislation that “NGTs […] can result in organisms with modifications equivalent to what can be obtained by conventional breeding methods or in organisms with more complex modifications“.

In addition to this generalisation, the use of the term “can” is also intriguing. It theoretically implies that this equivalence is not certain, or even almost improbable. There are several examples of plants that would be considered deregulated because they meet the criteria for the NGT1 category and yet could not be obtained by selection, except by waiting billions of yearsiv.

Another subtle shift is the change from “substantially equivalent” to “equivalent“. This wording is repeated in recital 14, which adds plants that occur “naturally” to conventional methods: “NGT plants that could also occur naturally or be produced by conventional breeding techniques and their progeny obtained by conventional breeding techniques (“category 1 NGT plants“) should be treated as plants that have occurred naturally or have been produced by conventional breeding techniques, given that they are equivalent and that their risks are comparable, thereby derogating in full from the Union GMO legislation“.

Equivalence, according to the European Commission

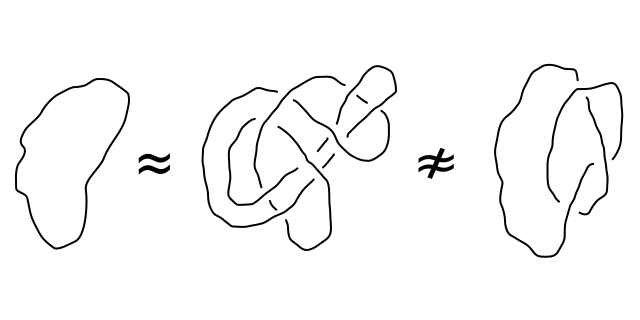

Beyond these abuses or semantic transformations from the conditional to the affirmative, from “certain cases” to “all cases“, or from “substantially equivalent” to simply “equivalent“, the European Commission therefore focuses its reasoning on the concept of equivalence.

Given the implications of the proposed deregulation, it is important to read the proposed definitions of equivalence carefully. For the European Commission, “a NGT plant is considered equivalent to conventional plants when it differs from the recipient/parental plant by no more than 20 genetic modifications“v. In simpler terms, it is different, but equivalent. It is also worth noting that what is referred to here as a “genetic modification” is a set of genetic modifications of different types. A genetic modification as stated in the definition of equivalence we have just seen can be a “substitution or insertion of no more than 20 nucleotides“, a “deletion of any number of nucleotides” or insertions, substitutions or inversions of certain genetic sequences.

To understand the absurdity of the reasoning proposed by the European Commission, let us consider the genetic modification of the “deletion of any number of nucleotides” type. An organism from which half of the genome has been removed in the laboratory – provided it is still viable – would therefore be “equivalent” to an organism with a complete genome, according to the European Commission…

The Council of the European Union takes the same line

For the Council of the European Union, the definition adopted in the negotiating mandate given to the country holding the Council Presidency is similar to that of the European Commission, but worsevi. For the Council, “a NGT plant is considered equivalent to conventional plants when it differs from the recipient/parental plant by no more than 20 genetic modifications per monoploid genome“. This clarification “per monoploid genome” means that, in the case of wheat for example, the number of genetic modifications included in the equivalence is no longer 20 but 120 (wheat has six copies of the genome or, in other words, six haploid genomes).

The European Parliament takes a hard line

For its part, the European Parliament has taken the argument to a rather unimaginable level. It states that “a NGT plant is considered equivalent to conventional plants if […]The number of the following genetic modifications, which can be combined with each other, does not exceed 3 per any protein-coding sequence“vii. What are referred to as “coding sequences” can be equated – for purely mathematical purposes – with the number of genes. In the case of maize, which contains 32,000 identified genes, the European Parliament therefore considers that a plant containing up to 96,000 genetic modifications would be equivalent to maize without genetic modification. If a genetic modification can be a substitution of 20 nucleotides, corn undergoing 96,000*20, or 1,920,000 nucleotide substitutions, will be declared “equivalent” to corn without genetic modification… Wheat, on the other hand, contains more than 100,000 genes, so 300,000 genetic modifications would be tolerated in deregulated GMO/NGT1 wheat, equivalent to 6,000,000 nucleotide substitutions to claim equivalence with non-genetically modified wheat…

This calculation can be roughly made today, but will potentially be even higher tomorrow, as the number of known coding sequences evolves with research, following the example of micro coding sequences that were still little known, if not unknown, ten years ago.

Deregulating a GMO wheat on the principle that it is, or may be, “equivalent” to conventional or natural wheat is, semantically speaking, a tour de force: declaring two fundamentally different plants to be equivalent. And even then, only in terms of genetic sequences, since legislators do not seem to be interested in epigenetic modifications, for example!

It is also interesting to note an additional paradox of pro-deregulation European legislators. All GMOs that are declared deregulated will have to be reported to the authorities. However, the authorities will have no way of verifying the claims made by multinational companies, as the Commission’s proposal does not make it mandatory to provide methods for detecting and identifying the genetic modifications that have been made. It considers that “in certain cases, genetic modifications introduced by these techniques are indistinguishable with analytical methods from natural mutations or from genetic modifications introduced by conventional breeding techniques“viii. The European Union would therefore choose to blindly trust multinationals to decide whether to deregulate a GMO…

i Eric Meunier, “More words, always words…”, Inf’OGM, 7 November 2025.

ii Eric Meunier, “When lexical confusion serves political purposes”, Inf’OGM, 12 November 2025.

iii Eric Meunier, “Directed, targeted, precise mutagenesis… Are these adjectives misleading?”, Inf’OGM, 17 November 2025.

iv Frédéric Jacquemart, President of the International Group of transdisciplinary studies (Groupement International d’Études Transdisciplinaires (GIET)), « Note pour le ministère de l’Agriculture », February 2025.

v European Commission, « ANNEXES to the Proposal for a REGULATION OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL on plants obtained by certain new genomic techniques and their food and feed, and amending Regulation (EU) 2017/625 », 5 July 2023.

vi Council of the European Union, « Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on plants obtained by certain new genomic techniques and their food and feed, and amending Regulation (EU) 2017/625 », 7 March 2025.

vii European Parliament, « Plants obtained by certain new genomic techniques and their food and feed European Parliament legislative resolution of 24 April 2024 on the proposal for a regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on plants obtained by certain new genomic techniques and their food and feed, and amending Regulation (EU) », 24 April 2024.

viii Whereas 7, European Commission’s proposal of July 2023 :

European Comission, « Proposal for a REGULATION OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL on plants obtained by certain new genomic techniques and their food and feed, and amending Regulation (EU) 2017/625 », 5 July 2025.