News

Directed, targeted, precise mutagenesis… Are these adjectives misleading?

Being precise, targeting and achieving one’s goal, directing a mutagenesis… these are adjectives that convey a sense of control and precision. However, on closer inspection, these adjectives mean nothing in a legal text. Because, in the European Commission’s proposal to deregulate a number of GMOs, they are not accompanied by their corollaries: targeted where? Precise to what degree? Directed by what or by whom?

In both 1990 and 2001, European legislators established that genetic modification techniques used to modify the genetic material of an organism in a way that does not occur naturally through multiplication and/or natural recombination resulted in GMOs. This definition includes both the method used to achieve genetic modification and the modification itself. But the legislator went further in its thinking.

Mutagenesis, in 1990 and then in 2001

The same legislator drew up a non-exhaustive list of techniques that produce GMOs subject to the requirements of the legislation. It cited, for example, techniques of ‘recombinant nucleic acid techniques’ consisting of inserting nucleic acid molecules into an organism in which they do not occur naturally.

Another technique was cited as producing GMOs: mutagenesis. In Directive 2001/18, this ‘mutagenesis’ produces GMOs that are not subject to the requirements of the legislation, but only in cases where it is used traditionally and with proven safety on the one hand, and on condition that it does not involve the use of recombinant nucleic acid molecules or GMOs on the other. This terminology was clarified in 2018 by the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) as not applying to mutagenesis techniques developed mainly after 2001, thus confirming that more recently developed mutagenesis techniques (since 2001 but also during a period priori to 2001) do not result in exempt GMOs eitheri. In 1990, as in 2001, the legislator therefore made a clear distinction between techniques involving the insertion of DNA sequences and what it then called ‘mutagenesis’.

Mutagenesis in 2025, according to the European Commission

In its proposal to deregulate many plant GMOs (and certain micro-organisms) in 2023ii, the European Commission discreetly introduced a broader legislative view of what mutagenesis is. It proposed to define ‘targeted mutagenesis’ as ‘mutagenesis techniques resulting in modification(s) of the DNA sequence at precise locations in the genome of an organism’.

Reading Annex 1, which the European Commission attached to the proposed regulation in 2023, it is clear that, this time, mutagenesis can involve the substitutions of nucleotides by other nucleotides, insertions (additions) of genetic sequences ‘of up to 20 nucleotides’ or deletions (losses) of sequences. Through a rather subtle rhetorical manoeuvre, the Commission also proposes that these modifications be cumulative. Substitutions or insertions of sequences can be added to each other without limit. This is a far cry from the 2001 version of ‘mutagenesis’, which did not cover sequence insertions…

‘Targeted’, ‘precise’ mutagenesis…

In addition, the European Commission adds the term ‘targeted’ to the term mutagenesis. It justifies this qualifier by explaining that ‘one or more modifications’ would be caused ‘at precise locations in the genome of an organism’. By referring to ‘one or more modifications’, the Commission is opening the door for multinationals to present plants as being genetically modified in a controlled manner, even though they have been obtained by trial and error, as shown by certain files submitted in the United States of Americaiii.

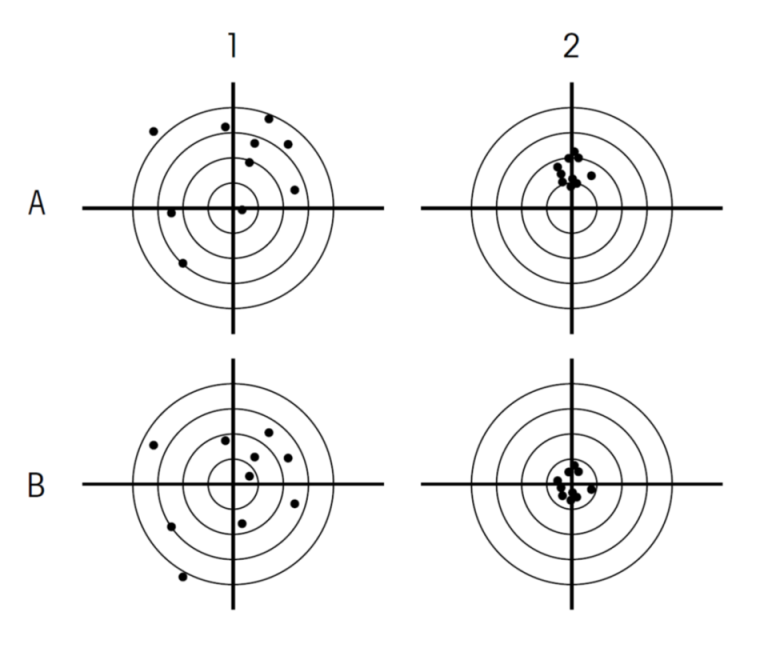

For its part, in 2024, the European Parliament did propose to replace the term ‘precise’ with ‘targeted’iv. The intention behind these words is to reassure: if the modification is ‘targeted‘, it means that it is controlled, even safe. But ultimately, without further clarification, what constraints would the term ‘targeted’ impose on a company? In principle, any application for authorisation of GMOs obtained by ‘targeted mutagenesis’ could be subject to this new regulation. A company could easily claim to have ‘targeted’ a particular sequence in an organism’s genome and could just as easily conceal the fact that it had to try 809 times before succeeding.

The added consideration that these modifications take place ‘at precise locations in the genome’ is also noteworthy. Although the term ‘precise’ suggests precision in the technique and/or technicians, this is not the case, as the term is not binding. By definition, a genetic modification obtained anywhere in a genome, whether in the initially desired location or elsewhere, will often be found in a location in the genome that is precisely identified a posteriori, i.e. after the first application of the claimed process. Like a car stopping at random anywhere between Marseille and Paris, once stopped, it will be in a precise location on the road, which will be described as precise since any car wishing to reproduce that exact route will also stop there.

A specific political aim too?

Given the vagueness of terms such as ‘targeted’ or ‘precise’ when used in conjunction with mutagenesis, the question of legislative issues arises. As we have already seen, a company will have no difficulty in claiming that a particular GMO has been obtained by ‘targeted mutagenesis’ with mutations occurring at a precise location in the genome. One example that springs to mind is the company Cibus and its description of its canola 5715. In 2013, this genetically modified plant was described as having been obtained by ‘directed mutagenesis’, with the company even using a term that is no longer part of the debate today, namely ‘oligonucleotide-directed mutagenesis’v. However, in 2018, the CJEU reminded everyone that this mutagenesis technique produces GMOs that are subject to the requirements of European legislation on GMOs. In 2020, Cibus changed its description and explained that its canola had in fact been obtained by a mutagenesis method called ‘somaclonal variation’, hoping to escape European GMO regulationsvi.

As this rapeseed has disappeared from the marketvii, the final outcome of a legal procedure in Europe will not be known, but it reveals how easy it is for a company to change the description of the same GMO. By using imprecise terms, European legislators are likely to make it even easier for companies to circumvent GMO legislation…

i Court of Justice of the European Union, « Case C‑528/16 », 25 July 2018.

ii European Parliament, Legislative Observatory, « 2023/0226(COD) Plants obtained by certain new genomic techniques and their food and feed », 5 July 2023.

iii Annick Bossu and Eric Meunier, « Les mots à la base de la stratégie des multinationales », Inf’OGM, le journal, n°173, October/December 2023.

iv See the proposed modification of article 3 :

European Parliament, « Plants obtained by certain new genomic techniques and their food and feed », 24 April 2024.

v Eric Meunier, « Colza Cibus : une mutation aux origines mystérieuses », Inf’OGM, 29 September 2020.

vi Eric Meunier, « Canola OGM : le gouvernement canadien au secours de Cibus », Inf’OGM, 10 November 2020.

vii Claire Robinson and Jonathan Matthews, « GMO company Cibus investigated for deceiving investors », GMWatch, 8 July 2024.