News

“Biotech Act” 2025: high-tech against farmers?

In 2025, the European Union is expected to adopt a “biotech act” aimed, among other things, at modernising agriculture through new technologies. At the same time, public policies, in particular the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), are guiding farmers towards ever more expensive and sophisticated mechanisation. As a result, a “high-tech” and soil-less agricultural model is taking shape in Europe, with the risk of increasing farmers’ indebtedness and marginalising small-scale farming.

Beyond the European Commission’s promises of innovation and competitiveness, the Biotechnology Act planned for 2025 will undoubtedly have a major impact on the European agricultural model. Commission President Ursula Van Der Leyen commented in July 2024: “this [initiative]will be part of a broader Strategy for European Life Sciences to look at how we can support our green and digital transitions and develop high-value technologies“i. However, by favouring digital solutions, and in fact biotechnological solutions rather than “green” ones, the Commission is accentuating the divide between large farms and small farms, while making farmers more dependent on technology.

A law that worries…

The “biotech act” of 2025, currently being prepared by the European Commission, is presented as a response to the climatic and economic challenges affecting agriculture. In a March 2024 communication, the Commission expressed its ambition to position Europe as a world leader in biotechnology. Margrethe Vestager, executive vice-president of the Commission, stated on this occasion: “We want to leverage Europe’s clear scientific edge in biotech, and turn it into commercial success “ii. To achieve this, the Commission plans to raise awareness of these technologies, speed up access to funding via the European Innovation Council and put in place an appropriate regulatory framework (i.e. in layman’s terms: less restrictive).

Among the promises of these technologies are the creation of new disease-resistant varieties, the optimisation of yields thanks to NGTs (New Genomic Techniques), notably Crispr-Cas9, and the reduction in the use of chemical inputs. However, behind these promises lies a less ideal reality. Biotechnology, particularly because it is protected by patents, increases farmers’ dependence on multinationals and threatens the very existence of farmers’ seeds. What’s more, the emphasis on digitisation and the “technologisation” of agriculture is pushing aside agro-ecological practices and solutions based on local know-how. This undermines sustainable agricultural models that are adapted to specific local contexts. This is particularly true of public support, such as that provided under the CAP, which is currently unevenly distributed. According to a report by France Stratégie, they should be redirected to give priority to supporting farms that adopt ambitious agro-ecological practices, such as organic farming. The idea is to align economic support more closely with environmental objectives, by rewarding farmers who limit their impact on nature while ensuring the long-term viability of their business. In France, the government is following a similar path by promoting digital agriculture, notably through the “Agriculture et Numérique” roadmap presented in March 2022, which aims to integrate digital technology as a pillar of the third agricultural revolutioniii. This policy includes tax incentives for the acquisition of connected equipment, as part of the France 2030 planiv. However, there is opposition to this approach. Farmers’ unions, such as the Confédération paysanne, are voicing their dissatisfaction with policies that they believe are unfavourable to small farmsv.

A CAP that drives people into debt

At the same time, public policies, in particular the CAP, are massively directing subsidies towards farms capable of investing in cutting-edge technologies: connected tractors, farm robots, drones and data analysis tools. These colossal investments are presented as necessary to improve productivity and make agriculture “intelligent“vi.

But for many farmers, this race for technology comes at a price: debt. According to recent figures, the level of lending to the agricultural sector continues to rise. Between 2021 and 2022, for example, it rose by 13%vii. These financial burdens often force small farms to sell their land to industrial operators, reinforcing land concentration and speeding up the disappearance of family farms. This logic of industrialisation is pushing Europe even further away from small-scale, diversified agriculture.

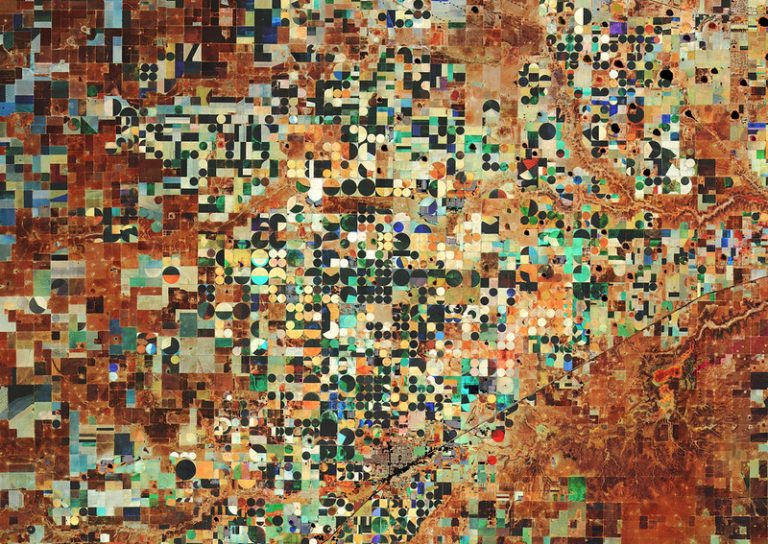

Disconnecting land and people

This new digital and biotechnological agriculture is also radically transforming the farming profession. Far removed from ancestral practices, farmers are becoming data managers, users of algorithms and robotised equipment. This gradual disconnection from the soil and nature poses a fundamental problem: can we really aspire to sustainable, robust agriculture by eliminating the direct link between man and his environment?

From an environmental point of view, the consequences of such a disconnection can be dramatic. The intensification of industrial monocultures, favoured by these technologies, is accentuating soil degradation due to the increased use of chemical inputs and is leading to an alarming reduction in biodiversity. In 2020, a reportviiiby the French Ministry of Ecological Transition and Solidarity showed that between 2009 and 2018, pesticide use had increased overall. Sales of insecticides have increased by a factor of 3.5, fungicides by 41% and herbicides by 23%. To date, agricultural technological innovations have not demonstrated their ability to support agriculture that respects regional specificities and natural cycles.

Alternatives for resilient small-scale farming

Faced with this technological headlong rush, there are alternatives. Agroecology, for example, offers practical solutions tailored to the challenges of climate change. Based on mixed farming, extensive livestock rearing and local know-how, it promotes sustainable, diversified and resilient agriculture.

To support this model, public funding needs to be channelled towards farms on a human scale, short distribution channels and the promotion of farmers’ seeds, rather than towards large-scale industrial farms. Some local initiatives, such as organic farming cooperatives and agroforestry projects, show that another path is possible.

Finally, a strict framework for biotechnology seems essential to preserve people’s food sovereignty. This means regulating patents, ensuring total transparency on environmental and health impacts, and genuine consultation with the public.

Choosing the future of agriculture

The biotechnology 2025 act and current public policies are pushing European agriculture towards a technological, digital and industrial model that is far removed from soil and people. This theoretical model, disconnected from the realities on the ground, guarantees neither the future of European agriculture nor the preservation of the environment.

Europe has a choice to make: to support small-scale farming that is rooted and resilient, or to persist in an above-ground approach dominated by technology and multinationals. This choice will determine not only the future of farmers, but also that of Europe’s food sovereignty and environment. Reinventing agriculture can be done by means other than robots and GMOs, by drawing inspiration from the soil, nature and the people who have worked it for centuries.

i European Commission, “Political guidelines for the next European Commission”, 18 July 2024.

ii European Commission, “Communication from the commission to the european parliament, the council, the european economic and social committee and the committee of the regions, Building the future with nature: Boosting Biotechnology and Biomanufacturing in the EU”, 20 March 2024.

iii Ministère de l’Agriculture, Dossier “Le numérique au service de la 3e révolution agricole”.

iv PACA Chamber of Agriculture, “Plan France 2030: a financial support scheme for the acquisition of innovative equipment”, 12 April 2022.

v Objectif Gard, “La Confédération paysanne démonstra le plan France 2023 de Macron”, 19 February 2022.

vi Ministry of Agriculture, “Launch of the France 2030 scheme to support investment by farmers “Equipment for the third agricultural revolution”: a tool to promote food sovereignty and ecological planning”, 1er March 2023.

vii Novethic, “Faced with the profession’s colossal debt, Coordination Rurale targets the banks”, 29 January 2024.

viii Ministère de la Transition écologique et solidaire, “Plan de réduction des produits phytopharmaceutiques et sortie du glyphosate: état des lieux des ventes et des achats en France en 2018”, May 2020.