A farmer’s opinion on agritech

Inf’OGM interviewed Stéphane Galais, a farmer in Ille-et-Vilaine (Brittany, France) with a 25-hectare farm producing milk and cheese. He is also national secretary of the Confédération paysanne. In this interview, he explains and analyses what agritech means to him.

Inf’OGM – First of all, what does the word “agritech” mean to you?

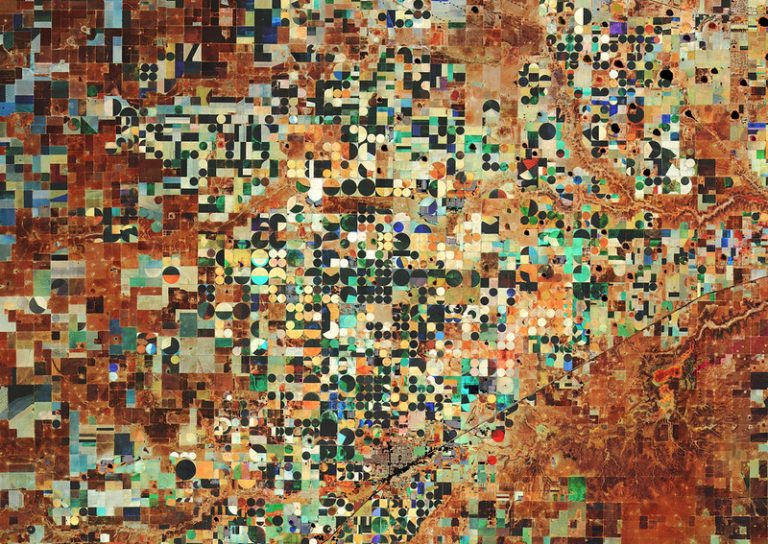

Stéphane Galais (SG) – For me, agritech is the combination of agriculture and technology. Agritech, or precision agriculture, another term that’s currently gaining ground, is all about robotics, digital technology and genetic transformations. But for us at the Confédération paysanne, the political project we’ve been pursuing since the 1990s is peasant farming. And in this political project, there is a desire for autonomy on farms, i.e. decision-making autonomy and technical autonomy. In our view, this political project is incompatible with the technological approach. But this is not a new phenomenon. For a long time now, we’ve been witnessing over-mechanisation on farms, which leads to a dependence, I would almost say an allegiance to an agro-mechanical, agro-industrial ecosystem that we don’t want. We don’t reject technology on principle, but it must be at the service of farmers and, more broadly, at the service of a societal project aimed at food sovereignty.

When we talk about technical autonomy, we basically mean having the capacity to repair, maintain and manage our machines… This know-how exists and could be threatened by the arrival of ultra-modern, super-powerful machines.

Agritech, then, is a far cry from farming know-how as we know it. Admittedly, it’s conceivable that these new skills could be acquired, but we’re still a long way from the skills and know-how of farmers, which are more closely linked to the management of living organisms or knowledge of living organisms, or knowledge of animals and their relationship with them.

In concrete terms, we’re already seeing this loss of autonomy with the arrival of robotisation, particularly on dairy farms. We see it because we have less control over the tools. These are complicated tools, some of which are patented and owned by certain companies that we will never be able to access.

Inf’OGM – Milking robots are a precursor to agritech. Do you have any feedback from farmers who use them?

SG – The first piece of information we have is that these robots don’t reduce the workload. It changes the working hours, without eliminating them completely. It changes the need to be at milking twice a day at a given time. The second feedback we often get is that these tools bring work into the home. In practical terms, this means that when you go home, you haven’t finished working, because the robot can send out work instructions. In the old days, when you’d finished milking, you’d go home. That’s it. Unless you had a sick animal. But there used to be a very clear dividing line between when you worked and when you were at home with your children. But now, at lots of times, the robot sends you messages to deal with malfunctions, such as a problem with cows that don’t want to ‘come in‘ to the robot, so the robot sends an alert… So that really changes the perception of work and the relationship with time.

This relationship with time is fundamental for us at the Confédération paysanne. For us farmers, time is conditioned by life, and is in direct opposition to capitalist time and Taylorism. The machine changes this relationship with time.

Inf’OGM – Another advantage put forward by the promoters of agritech is better weed management...

SG – In fact, what creates a real problem with weeds? Or, more broadly, the health issue? It’s the intensification of agriculture, the intensification of production. In other words, we want to produce a lot on a small area or on a large area, but with few people. We are witnessing a real concentration of agriculture. And that inevitably creates management problems. So we’re trying to find solutions to these problems through technology. But in fact, that’s not the problem. The problem lies with the system of concentration and intensification. We can see that in a more extensive system, a more rural system, a more agro-ecological system, we manage to deal with these problems outside the field of technology, because we manage to put the human element back in. We can also work on the synergies between living organisms, so that the system is more in balance. In this context, in concrete terms, technology is a false solution to a fundamental problem, a systemic problem. It’s a band-aid on a wooden leg.

I always take the example of carrots. It’s a complicated crop because it’s very difficult to manage in terms of competition with weeds. But on my farm, I grow 30 metres of carrots in a diversified system. So I can weed as I go along, spending just two hours on it in the end. So in a system like that, it’s not a problem. But if you have 30 hectares of carrots in monoculture, you have a real weed management problem. So either you hire an army of people and their work is degraded, because it’s monotonous and hard work, often poorly paid, or you use technology.

The political project is to install a million farmers and also to have this approach to work effort, to rethink work in a system that is certainly more complex, but also more humane. The priority is to get farmers settled and to ensure that they are properly paid on the basis of the price of their produce, i.e. a price that covers production costs, income and social protection.

Inf’OGM – One of the criticisms of agritech that we often hear is that it’s expensive…

SG – Technology is never neutral, unless it emanates from a desire, from a farmers’ collective. But this is never the case. In fact, the initiative for technique and technology always comes from the agro-industry and is put at the service of their profits. The aim of technology is to maintain a productivist system and guarantee profits and margins for the industry. It’s a kind of vicious circle, since it also creates a dependence on mechanics or robotics and increases investment in farms. Yes, it’s clear that all these new tools are costing farmers crazy amounts of money. Not only is there the initial investment, but also the running costs of these tools. As a result, their income is what it is, but it’s also very closely linked to a price determined by the market and by the powerful. In fact, you find yourself trapped in a kind of proletarianisation of agriculture: you no longer really control your production tools. And we see it every day: over-investment creates unhappiness. It’s another vicious circle: to recoup these investments, you also have to increase your productivity, increase volumes… This is where we come back to the problem mentioned earlier: it encourages the intensification and enlargement of farms… In the end, there are fewer and fewer people on the farms. All this contributes to the disappearance of farmers from the countryside.

And this is nothing new! As the agronomist Marcel Mazoyer has shown, with each technical and technological revolution, a large number of farmers disappear. There’s a simple reason for this: only those with the capital can access the new technology. So it’s also a way of pitting farmers against each other in terms of access to techniques and technology.

What’s more, we’re also forgetting one historical fact, which is that the advent of mechanisation was to the detriment of farmers and often even against their will. At the end of the [Second] World War, food production was completely balanced. It was really a desire for industrialisation that was put in place, not a desire on the part of farmers.

Inf’OGM – But doesn’t technology that improves productivity also improve farmers’ incomes and lower prices for consumers?

SG – And who benefits from increased productivity? You have to look closely at what a price is. In the price of a carrot, for example, the share of agricultural materials is not essential. The rest is linked to processing and distribution. At the Confédération paysanne, we believe that increasing productivity and lowering production costs in no way guarantees a better distribution of value. In fact, the problem of the price paid by the consumer also stems from the distribution of value between distributors and processors. And there is no guarantee that they are prepared to share this value. I don’t see any direct correlation between lower [production] costs and lower shopping-cart costs. In any case, that’s not what we’re seeing. It’s not a direct effect, in any case, until we have properly distributed the value between everyone and better controlled the margins of distributors and processors.

Inf’OGM – So you’re opposed to all forms of technology?

SG – In the political project of the Confédération paysanne, there is this desire to control production tools, to reappropriate them and, therefore, to be at the initiative of these tools. In fact, we want the tools to be of real use to the farmers and to be thought out by them. So yes, we’re getting closer to the project put forward by the Atelier paysan, which is a real political project for society and a real reflection on mechanisation. I’ll say it again: technology is never neutral! That’s a myth.

I’d like to share a very personal reflection with you. I keep imagining what agriculture might have looked like today if we’d been able to limit tractor power to 60 horsepower. But just by doing this mental exercise, you can see very quickly that we could have maintained a completely different bocage, a completely different size of farm, a completely different type of production. The mastery of tools, of technical tools, is also the aim of agriculture. And that’s a collective choice, one that must also and above all be made by farmers.

Technology must be combined with a real reflection on the meaning of work and on the arduousness of work.

I was also saying that mechanisation was neither desired nor organised by the peasants, but on the other hand, the peasants jumped on the bandwagon. Behind mechanisation was a promise of emancipation, particularly social emancipation. Farmers have always been somewhat downgraded and devalued by society. Mechanisation was modernity. In any case, this was the association that was made, that was promoted. It was also necessary to get people away from the animals. It’s clear that on livestock farms, particularly in Brittany, people have gradually moved away from where the animals live. And this distance is a real cause of suffering.

When you’re a farmer, you’re also motivated by this desire for intimacy or proximity with living things. And, on the contrary, this link with living things prevents the extractivist relationship with living things that agriculture has become. It’s very complicated to create intimacy with your animals and at the same time over-exploit them.

In concrete terms, all the people who are trying to re-create agro-ecological systems that take greater account of and have a better understanding of living things are gradually moving away from industrial farming. Bringing the emotional, the sensitive, back into the relationship that we can have in our profession as farmers inevitably distances you from the extractivist and exploitative relationship that we know in the agro-industrial world. In industrial pig farms, the animals are so treated as objects that we no longer talk about animals. We talk about weight, we talk about livestock units, we talk about indices, and so on. So there is a commodification of living things in the industrial context. Conversely, there is a reawakening of awareness of the link in the agro-ecological farming environment.