News

Seeds regulation: the industry weighs in the balance

At a time when the European Union is preparing new regulations on seeds, a look at the meetings between MEPs and the various stakeholders indirectly shows the weight of the multinationals in these procedures. This raises questions about the imbalance in the representation of these parties and the potential consequences for small seed companies, farmers and peasants.

In July 2023, the European Commission launched a reform of the regulations on plant reproductive material (PRM), known as the “seeds regulation“i. If adopted, the text proposed by the Commission would impose new practices on small non-industrial players and influence crop diversity. During the tripartite negotiation process – still ongoing between the European Parliament, the Council of the EU and the European Commission – various “interest groups” (industrialists, NGOs, trade unions, etc.) meet MEPs to defend their positionsii. These exchanges are recorded in a public registeriii, which is intended to guarantee transparency, but which reveals nothing about the content of the exchanges. This register reveals a clear predominance of industrialists (or their affiliates and representatives) over NGOs, organic farming players and farmers’ unions, raising questions about the balance and impartiality of decisions.

Typology of interest groups

The interest groups that met with MEPs in connection with the MRV regulationiv can be divided into two categories, depending on whether they belong to or are associated with multinationals, or traditional seed production and farming.

The first category includes companies such as KWS and Limagrain, and trade unions or professional organisations close to agricultural industries, such as Copa-Cogeca (a European farmers’ union), Euroseeds (representing the European seed industry) and the Bayerische Pflanzenzucht- und Saatbauverbände (BPS, an organisation bringing together Bavarian plant breeders and seed multipliers). It also includes, on the fringes, the Association Générale des Producteurs de Blé et autres céréales (AGPB), which represents the interests of French straw cereal producersv. In its position on the new MRV rules, Euroseeds, for example, which also represents KWS, Limagrain and other major companiesvi, defends a standardised industrial seed production systemvii. Also in this category are consultants such as the Hungarian firm PRM CE Kftviii, which specialises in lobbyingix. Although this firm states that it works for industry, particularly agri-business, it does not mention its clients.

The second category includes players defending non-industrial (or less industrial) agriculture, such as Arche Noah and the Demeter federation, associations of small non-industrial players, such as the Irish Seed Savers, and those promoting organic agriculture (OA), such as IFOAM. A farmers’ union, ECVC, also took part in these meetings. This category of players defends more local models, centred on the environment and the rights of small seed growers and farmers.

Between these two poles, certain players who contributed to the meetings, such as the Community Plant Variety Office (CPVO)x, although officially neutral, tend to favour industrial interests, while the European institutions, such as the Commission, often oscillate between different interests depending on the subjects dealt with. We have also placed the ONF (Office National des Forêts) in this category.

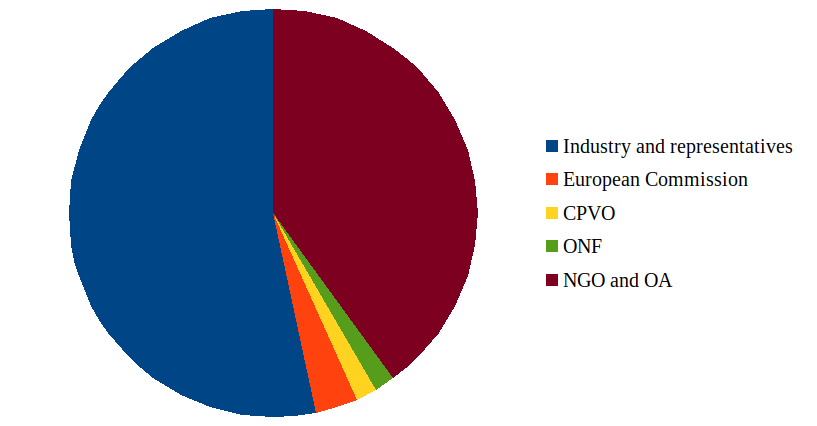

Imbalance in stakeholder representation

The data available on the European Parliament’s transparency platform reveals an imbalance in stakeholder representation (see figure below). Of the 58 meetings listed, MEPs met more frequently (32 times) with industry and its representatives (trade unions, professional organisations and consultants, in blue) than with NGOs, organic farming representatives or farmers’ trade unions (in purple) with 24 meetings. This imbalance is accentuated by the European institutions, the CPVO and the Commission, which, as mentioned above, are more inclined to defend the interests of industry than small seed producers or farmers. Like the International Union for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants (UPOV), of which it is a member, the CPVO favours the seed industry and ‘commercial‘ breeders by protecting their ‘innovations‘ through plant breeders’ rights. This position, criticised by small seed companies and farmersxi, reinforces the power of large companies to the detriment of small seed companies and farmers.

Herbert Dorfmann, the rapporteur on this draft MRV regulation, held 18 meetings with industry and its representatives, compared with 9 meetings with NGOs. Herbert Dorfmann is a member of the European People’s Party (EPP), historically favourable to the interests of agribusiness and regularly positioned to defend positions aligned with those of industry. This position can be seen in discussions around regulation, where industry representatives campaign for simplified rules favouring the standardisation of seeds and their protection by patents.

This asymmetry in the number of meetings also illustrates a dynamic in which industrial groups, thanks to their resources, networks and ability to mobilise, are able to carry more weight in discussions. Such industrial influence could have a major influence on the direction of legislation, which would mainly benefit large companies, to the detriment of environmental concerns and small-scale farmers. The power of the lobbies risks marginalising the latter in a system that favours standardisation and intellectual property to the detriment of diversity and fair access to seeds.

Financial inequality of forces

In Europe, organisations such as Corporate Europe Observatory (CEO) highlight the issue of lobbying by producing reports, such as “Loud Lobby, Silent Spring”, which denounce the influence of industrial interest groups on European environmental and agricultural policiesxii. CEO has developed a tool, Lobby Facts, indicating the lobbying expenditure of various players. For example, in 2022, Euroseeds spent between €1.75 and €2 millionxiii and Cogeca between €700,000 and €800,000xiv. In 2019, Euroseeds was already spending nearly €1.13 millionxv, while in the same year Arche Noah spent around €75,000 (no data for subsequent years). In other parts of the world, lobbying practices may be governed by what are reputed to be stricter transparency rules. In the United States, for example, the Lobbying Disclosure Actxvi imposes detailed reporting obligations on lobbying activities, more frequent declarations of such activities and stronger penalties, thus allowing for stricter public controlxvii .

Impact on “small players” and biodiversity

Regulations that are too favourable to the practices of industrial multinationals alone could have serious consequences for farmers, non-industrial seed companies and peasants. Rules that directly or indirectly favour patented seeds would increase or even complete farmers’ dependence on large companies, compromising their autonomy and economic sustainability. Furthermore, limited access to traditional seeds would reduce their options, while biodiversity, a key element in agriculture, would be threatened by standards favouring standardised and patented varieties.

By favouring standardised and patented varieties, regulations could reduce the use of local seeds, which are essential for maintaining the phytogenetic diversity of crops. This diversity is crucial to the resilience of agriculture in the face of various biotic and abiotic stresses. Players such as La Via Campesinaxviii and IFOAM are warning of these risks and calling for regulations that protect traditional seeds and encourage agro-ecology, rather than reinforcing the monopoly of multinationals.

Regulations with crucial issues at stake

With the European Commission’s proposed regulation, small farmers risk losing essential rights to protect, select and exchange their own seeds and associated knowledge, and to access a commercial supply of seeds adapted to the diversity of their needs and contexts. This situation would directly threaten their livelihoods and compromise agricultural biodiversity, which is crucial to global food security. It is imperative that European legislation protects these key players, who are indispensable to sustainable and diversified agriculture.

Following its adoption at first reading by the European Parliament, the text on seed regulation has now passed into the hands of the Council of the EU, which has just issued a revised version. A “trilogue“, a negotiating mechanism bringing together the European Commission, the European Parliament and the European Council, could now be launched, although a second reading in Parliament is still possible.

i Denis Meshaka, “EU – “Seeds”: the other proposal in the legislative package”, Inf’OGM, 3 October 2023.

ii Concerning the publication of meetings between the Member States of the Council of the European Union and interest groups, this information is generally available on the official websites of the Permanent Representations concerned.

iii European Commission, Transparency Register.

iv Legislative Observatory, “Production and marketing of plant reproductive material in the EU” , Transparence (consulted on 29 November).

v AGPB (Association Générale des Producteurs de Blé et autres céréales – General Association of Wheat and Other Cereal Producers).

vi Euroseeds, Members (accessed on 10 December 2024).

vii Euroseeds, “Euroseeds raises serious concerns over COMAGRI vote on new rules for Plant Reproductive Material”, 19 March 2024.

ix Lobby Facts, PRM Cee Kft (consulted on 2 December 2024).

x CPVO: Community agency that implements and applies the Community plant variety rights system. It issues plant variety certificates or PVCs.

xi Frédéric Prat, “Quand la loi paralyse les paysans… au-delà de son contenu”, Inf’OGM, 20 October 2022 (in french).

xii CEO, “A loud lobby for a silent spring – The pesticide industry’s toxic lobbying tactics against Farm to Fork”, March 2022.

xiii Lobby Facts, “Euroseeds”, 2022 (accessed on 2 December 2024).

xiv Lobby Facts, “Cogeca” (accessed on 2 December 2024).

xv Lobby Facts, “Euroseeds”, 2019 (accessed 2 December 2024).

xvi Government of the United States, “Lobbying disclosure”, 19 December 1995.

xvii Haute Autorité de la Transparence de la Vie Publique, “Tableau extrait de l’étude comparative des dispositifs d’encadrement du lobbying”, October 2020 (in french).

xviii Guy Kastler, “Seed marketing reform: freeing cultivated biodiversity or patented GMOs?”, Inf’OGM, 22 February 2024.