In the face of technological development, should we take the time to reflect on the bigger picture?

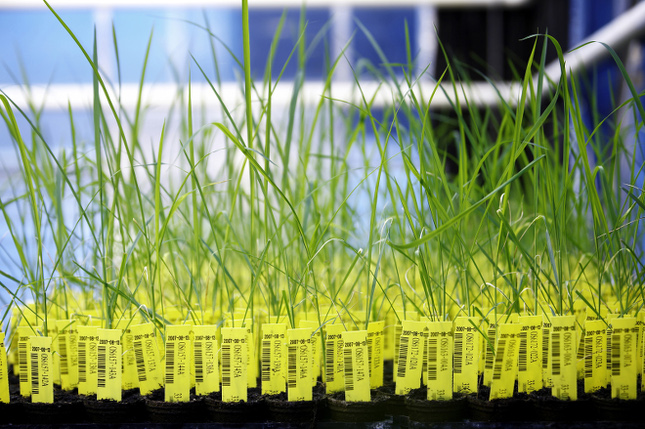

The development of GMOs, of the digitisation of living organisms and of the “biocontrol” are indicators of multinationals’ growing ambitions to appropriate living organisms, but not only. It is also, if not above all, a technological development which, once adopted, has a major impact on the global system that constitutes our societies and their environment. The changes are so significant that Frédéric Jacquemart refers to them as “systemic disruptions“. These disruptions should motivate our societies to adopt a global approach in order to better prepare and accept the necessary emergence of other “viable structures”, to use his wording.

Technologies generate increasingly powerful means of action on the systems in which we live. However, the assessment of the effects of these technologies is limited to the direct consequences of their products (e.g. a GMO on a particular group deemed relevant, such as a laboratory rat clone, the Eisenia fetida worm, etc.).

Complex systems, such as ecosystems and societies, are maintained through their organisations, which have been built up step by step over the course of evolution. Artificially modifying these organisations creates a major risk, which can even threaten the very survival of these systems, of which we are a part. However, this issue, which surpasses all others in importance, is simply not taken into account in the current assessment of technological risks!

For forty years, Frédéric Jacquemart has been desperately arguing that technology should no longer be developed blindly with regard to what constitutes our common destiny.

A first example of this global, systemic approach was given in the opinion piece “Biodiversity and stability of natural systems: what are the impacts of GMOs?”i. Today, Inf’OGM is publishing a second opinion piece, introducing another aspect, this time societal, of this blind technological production. It is not intuitive that GMOs could contribute to a surge in systemic violence, and yet…

Introductory note on the global (systemic) approach to disruptive and reactive violence

Author’s note: this note is extremely short and therefore inevitably appears simplistic and dogmatic. Its purpose is not to demonstrate, but merely to draw attention to this global, systemic approach, which can be developed and justified at length.

We live in complex adaptive systems (ecosystems, societies, etc.) on which we are totally dependent. These systems can be represented by networks of interactions between elements. This is an approximation, but it is already very useful.

These systems, which arise from the interactions between elements, have their own dynamics, organisation and evolution. These dynamics, organisations and evolutions are not the sum of individual interactions, but are a (strong) emergence from these interactions, which cannot be reduced to them.

In return (recursively), the organisations of the systems act on the elements and their connections, thus enabling the system to continue.

Primate groups are limited in number. Groups of “native” humans are limited to an average of 150 individualsii. Beyond that, there is division. However, we live in societies of tens of millions of individuals. Therefore, to ensure the cohesion of such societies, many things must be shared: language, symbols, customs, beliefs, stories, ethics, values, institutions, education, etc., at all levels (fractal organisation) and in a consistent manner.

These systemic constraints on individual behaviour are extremely strong, but this does not detract from free will, which, on the contrary, is made possible by these restrictions, without which humanity would not exist. Even groups smaller than the “Dunbar number” have collective constraints. Moreover, on our scale, the space for freedom within these constraints is enormous. We are not slaves to the system. In the same way, gravity is a constraint imposed on all bodies, but it is permissive of life and allows immense freedom. Having to breathe is also a constraint, and so oniii.

Very importantly, as we shall see, the vast majority of this coherence is necessarily achieved through the unconscious.

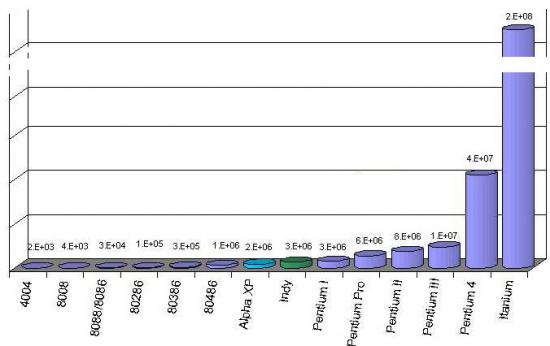

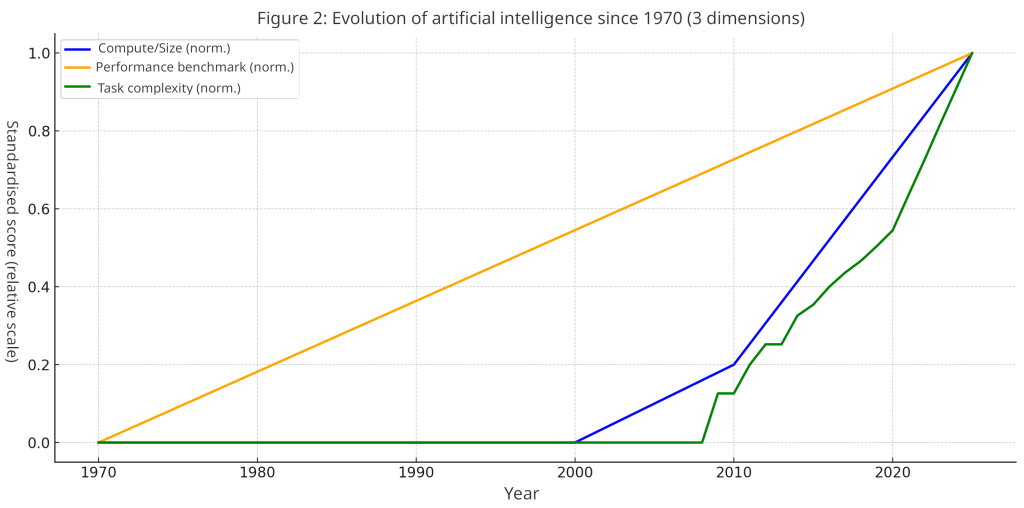

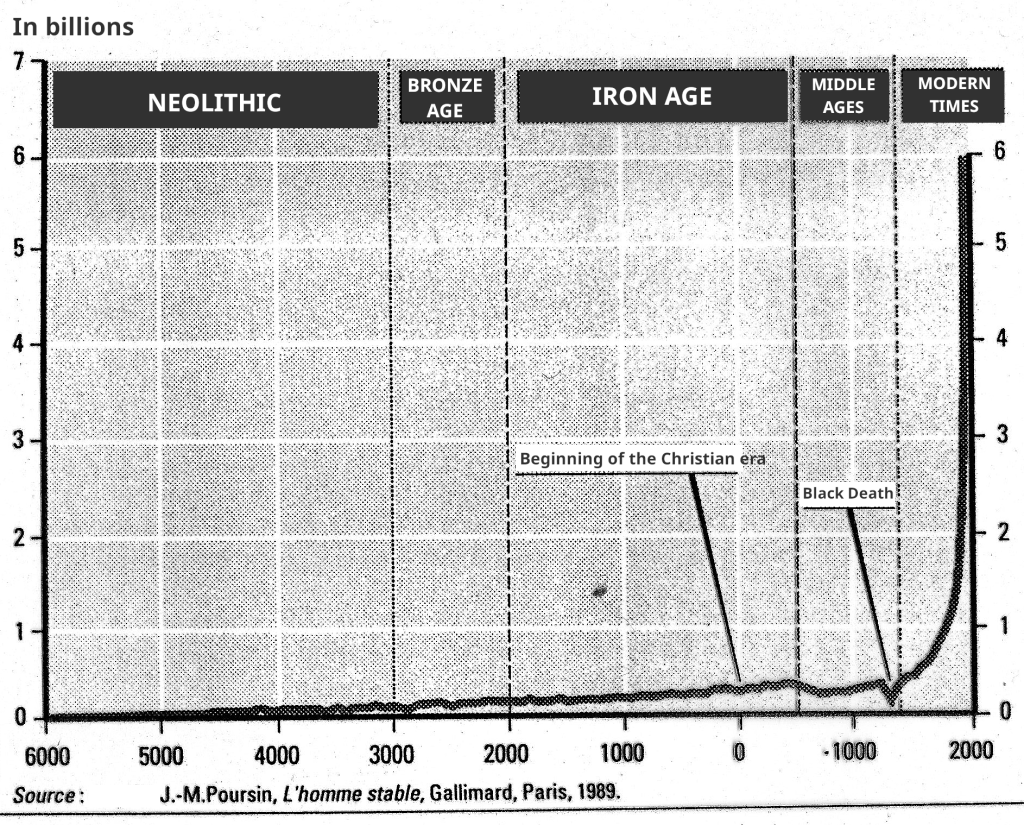

The framework for this discussion is based on the evolution of Western culture or civilisation (globalised, which is important). In order to represent it quantitatively on a graph, discrete parameters are requirediv. We can use very significant and structuring technological developments, such as the power of microprocessors (Fig. 1) or artificial intelligence (AI) (Fig. 2), or the evolution of a global result of technological development such as demographics (Fig. 3). Broadly speaking, and this will come as no surprise to anyone, this evolution is roughly exponential. This means that after a very long period of very little change (on a global scale), there is a phase of very rapid growth, which tends towards infinity. We are at the point on the curve where the rate of growth is enormous and where even a tiny advance in time leads us to infinity, which is clearly unreachable. This fact has been highlighted by many people, but has not been taken into account by decision-makers (nor by most NGOs, for that matter…). Yet it clearly means that the cultural engine of this civilisation (once again, globalised) is inevitably crumbling. It can be shown that this process of crumbling is already underway.

Whether one values the principles and other elements that have sustained it (work, family, homeland, patriarchy, etc.) or rejoices in seeing them crumble, in any case, it is not a choice: Western civilisation is coming to an end and there is no way to save it. The question is therefore not one of choice, but rather of preserving the possibility of allowing one or more other civilisations to emerge, and this possibility depends on preventing the reactionary violence generated by the systemic disruptions resulting from these profound changes.

Without going into detail, let us take the example of the unprecedented increase in the speed of change of society. Faced with such changes, not everyone reacts at the same speed or in the same way. And this is true in different contexts: some people will be very comfortable and will even demand faster computers or AI, but will be uncomfortable with changing social mores, for example. The speed of evolution of a complex system is not a descriptive parameter, but a component of the organisation of the system itself. Significantly accelerating or slowing down such a system disrupts its organisation, to the point of possibly destroying it. Here, this leads to the breakdown of the bonds that generate the organisation of society and the formation of new ones, with the creation of islands that are increasingly separated from each other, generating their own ethics, language, myths, etc. The alteration of sociological coherence processes means that, even though we are only at the beginning of this process, many countries have already become ungovernable and new forms of violence are taking hold: clan violence caused by systemic disruption and violence with no other motive than a visceral reaction to a loss of being meaning.

Let us not forget that the dynamics of social systems are expressed through the unconscious of individualsv. The erosion of the system unconsciously pushes individuals towards violence, which in turn increases the erosion. Positive feedback loops quickly become uncontrollable: this is a matter of major urgency.

Even though the unconscious accounts for the vast majority of intellectual activity and often prepares and makes decisions, the conscious mind interacts closely with it (again, recursion). Without going into this area, which is very important to our subject, let us say that the conscious mind has the ability to become aware of the unconscious’s output and can oppose it, at least in some cases. If we understand, even roughly, how society functions as a complex system and that its evolution normally generates violent impulses, we can recognise and reject these impulses when they arise. This will not hinder the process of erosion of the current dominant culture, but it will allow us to move on to other viable structures. What’s more, it will enable us to enjoy what will undoubtedly be a complicated but exciting phase of cultural metamorphosis.

NB: we have called this exciting adventure “the great epic” and introduced it in a video. You can contact the author at grandeepopee@orange.fr.

i Frédéric Jacquemart, “Biodiversity and stability of natural systems: what are the impacts of GMOs?”, Inf’OGM, 26 November 2025.

ii Dunbar, R.I.M., “Neocortex size as a constraint on group size in primates”, Journal of Human Evolution 22(6), pp. 469–493, 1992. There is a wealth of literature on this subject following this article.

iii For further reading (and improvement), see the important concept of “enablement” by Giuseppe Longo and Maël Montévil:

Giuseppe Longo, Maël Montévil, “Extended criticality, phase spaces and enablement in biology”, Chaos, Solitons & Fractals, Emergent Critical Brain Dynamics, 55, pp.64-79, 2013.

iv Parameters in the common sense of the term, not mathematical.

v This refers to the unconscious in neuroscience, which differs from that in psychology and psychoanalysis.