News

Illegal cultivation of GM soybeans in Tunisia revealed by DNA tests

Presented as a response to the feed crisis, a new crop is quietly taking root in Tunisian fields. Behind the soybeans, genetically modified seeds are being introduced without regulation and amid total institutional silence.

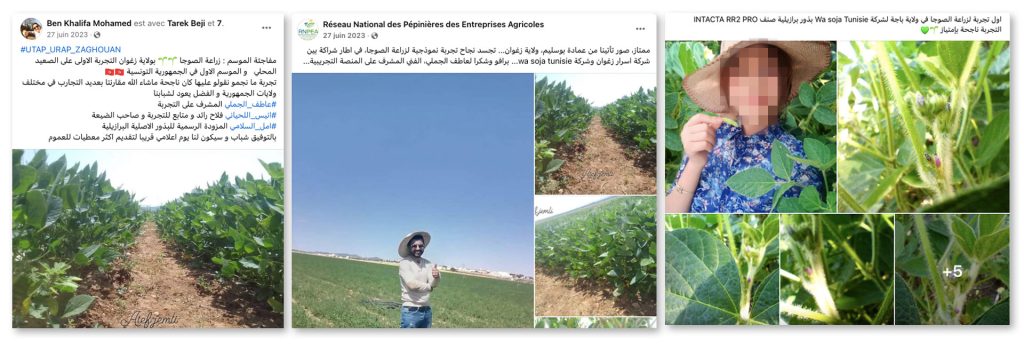

“Surprise of the season: first experiment with soybean cultivation in Tunisia, in the governorate of Zaghouan.” In June 2023, Mohamed Ben Khalifa, vice-president of the URAP, the regional branch of the Tunisian Union of Agriculture and Fisheries (UTAP) – the country’s leading agricultural union – in Zaghouan, proudly posted on his Facebook account photos of lush green soybean plants, sown for the first time a few months earlier in the fertile soil of Bir Mecherga (Zaghouan), in the north-west of the country.

A young agricultural technician, Atef Jemli, who supervised the experiment, also shares his optimism on his page, posing with a smile in front of the same field: “To all those who doubted the success of the experiment […] the results are fantastic“.

The news quickly spread on social media. For several months, the trend took hold and online agricultural circles seemed to be snapping up these new seeds. The reason given by the promoters of this new culture is to respond to the crisis in fodder resources used to feed livestock, which has been affecting the agricultural world for several years.

“The message we want to send is that it is possible to grow soybeans locally in Tunisia at low cost […] we are calling on the Tunisian government to invest in this sector,” said the representative of the regional union of agriculture and fisheries (URAP) of Zaghouan in a filmed interview. “We use drip irrigation, which requires very little water,” he added. The promotion of this promising crop is even being relayed by public television.

What everyone fails to mention, however, is that these seeds are in fact genetically modified (GMOs) and resistant to various herbicides, as revealed by laboratory analyses carried out by Christophe Noisette, a journalist specialising in GMOs, and journalists from inkyfada. Cultivated since the late 1990s, genetically modified crops (GMOs) are a new tool for intensive agriculture. Limited to a few species (maize, soya, cotton and rapeseed), they are mainly grown in North and South America and banned in most European countries due to their proven negative impacts1 . These herbicide-tolerant varieties have de facto increased the amount of herbicides sprayed, with all the consequences this has for human health, fauna and flora.

GM soybeans in Tunisia: silence, they’re growing

The experience in Zaghouan is not an isolated case. Across the country, particularly in the fertile regions of Béja and Jendouba, initiatives to introduce soybean cultivation multiplied between 2023 and 2024. These foreign seeds are readily available on market stalls, with no controls in place.

Information meetings and press conferences are also being organised by the URAP in several regions, such as Sidi Bouzid, with a view to encouraging farmers to grow soybeans to combat “difficult fluctuations […] and achieve self-sufficiency in livestock feed“. In its response to requests from inkyfada, the national office of the UTAP, through Mnawar Sghairi, director of the animal production unit, nevertheless distanced itself from this emerging practice: “These are isolated and amateur initiatives“. Mohamed Ben Khalifa, from URAP Zaghouan, did not wish to respond to inkyfada’s requests.

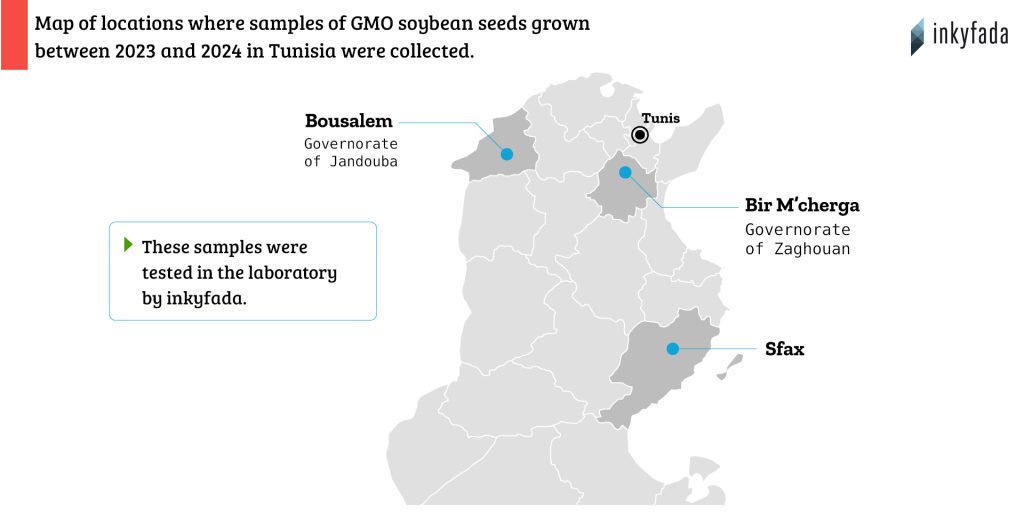

Through laboratory analyses carried out in Tunisia and then in France on three samples of soybeans taken from the regions of Boussalem (Jendouba), Zaghouan (Bir Mcherga) and Sfax, our investigation reveals the GMO nature of these seeds distributed to the Tunisian farmers we met.

There are two types of genetically modified crops currently grown worldwide: those that are genetically modified to tolerate herbicide spraying (e.g. Roundup) and those that produce an insecticide (Bt plants).

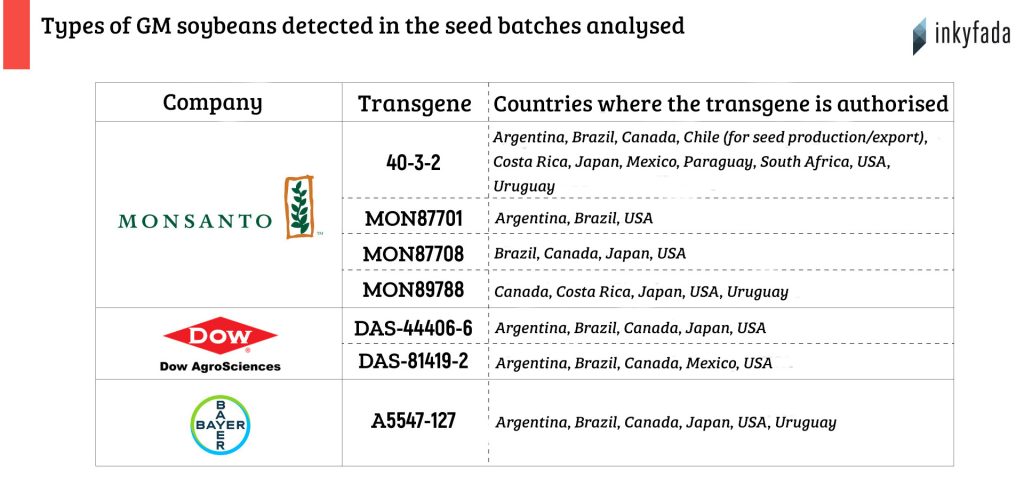

The first analysis, carried out in Tunisia, confirms the transgenic nature of these batches. The second, carried out in France, identifies the modifications more precisely and determines that the soybean samples harvested are tolerant to several herbicides (glyphosate, glufosinate-ammonium, 2, 4-D and dicamba) and produce several insecticides against lepidoptera (butterflies). These transgenes belong to several multinational biotechnology companies: Monsanto (Bayer), BASF and Dow AgroSciences.

France, for example, has banned the cultivation of Bt GM maize, arguing that it has too broad an insecticidal effect, since non-target insects are still killed. Specifically, it is currently impossible to draw any conclusions about human health, as the assessment protocols are not designed to determine safety or harmfulness. The Ministries of the Environment and Agriculture have not responded to requests from inkyfada.

The sorcerer’s apprentices of GMO soybean cultivation

Among the distributors of these GMO seeds in Tunisia, one “company” in particular is the subject of much praise from apprentice soybean farmers: WA Soja Tunisie, a supplier of “original Brazilian seeds“, as the organisation describes itself. Based in the governorate of Jendouba, it promotes its genetically modified Intacta RR2 Pro soy seeds, imported from Brazil, via its Facebook page, which has now been deleted. This brand was developed by Monsanto – since acquired by the agrochemical multinational Bayer – and contains two of the transgenes detected in our analyses.

Intacta RR2 Pro is a GMO that enables “tolerance” to glyphosate, the active ingredient in Roundup, and produces an insecticide against lepidoptera, the main butterfly pests in South America. The cultivation of Intacta RR2 Pro seeds is only authorised in South America (Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay). In Brazil, it now accounts for around two-thirds of the soybean country’s genetically modified crops2 .

At WA Soja Tunisie, Amal Sallami, a young woman from Jendouba, has an academic profile that is unusual for a farmer: she has a degree in climate change from Earth University in Costa Rica and Georgetown University in Qatar, is an adjudicator at the International Centre for Dispute Resolution (ICDR) and a category A judge at the International Court of Justice.

The young farmer had published a soybean cultivation training certificate issued by FEMARH (Foundation for the environment and water resources of the state of Roraima) in Brazil – a document of dubious authenticity, as the stamp differs from the one on the official copy available online.

In 2020, she participated in a symposium organised by the “Strategic Committee for Soybeans in Brazil” and was also invited to speak remotely at a symposium organised in Paraguay and funded by multinational agro-industrial companies, such as Corteva, a giant in the production of plant protection products and agricultural seeds.

During 2023-2024, she also hosted a number of events organised by regional branches of the UTAP to raise awareness and encourage farmers to grow soybeans, before disappearing from social media and ceasing all promotional activities. When interviewed by inkyfada, she never wished to reveal the precise origin of the seeds distributed to farmers, nor the identity of her “boss“.

Just as opaque as its manager, WA Soja Tunisie also abruptly disappeared from social media in 2024, after having been very active. Its existence can no longer be found online, it has no official premises and is not listed in the national register of companies.

Institutional uncertainty on GMOs: a door open to a fait accompli

In Tunisia, there is currently no legal framework governing the use of GMOs, and the few attempts to regulate the import and use of these transgenic seeds have all failed. A draft law on biosafety was proposed in 2014, resulting from a joint programme of the United Nations Environment Programme and the Global Environment Facility, for which the country received nearly $1 million3. Despite these significant resources, no law has been formally adopted.

However, Tunisia ratified the Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety in 2002 and is therefore required to control the use of GMOs and reduce the risks posed by biotechnology to biodiversity4 .

But in the absence of a regulatory framework, legal uncertainty persists and raises the question of the legality of GMO imports, which, in the European Union and many other countries, must be assessed and authorised before importation.

“In the absence of regulation, there is no obligation to carry out such controls or to put in place measures to prevent the risks that GMOs may pose,” comments Rim Mathlouthi, an activist for sustainable and responsible agriculture and former president of the Tunisian Permaculture Association.

The National Gene Bank, one of whose main missions is to preserve biological heritage, has been approached on several occasions. Although it has received, on a voluntary basis, samples of GM soybeans collected by inkyfada teams, it has not followed up or communicated any analysis results. Soybeans are strictly prohibited from cultivation, regardless of their nature: no soybean variety is listed in the official seed catalogue. “It is therefore not supposed to be grown in Tunisia,” says Fethi Ben Khelifa, spokesperson for the UTAP, a farmer who can only grow varieties that have been previously analysed by the state services.

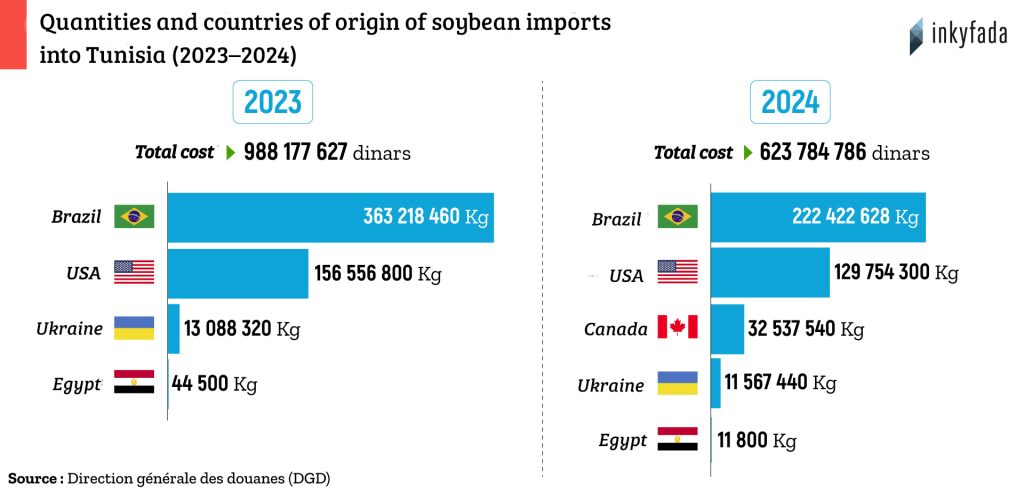

Tunisia already imports large quantities of soybeans – nearly 400,000 tonnes in 2024 – mainly from Brazil, the United States and Argentina, where more than 95% of soybeans grown are genetically modified, making it highly likely that imported soybeans are GMOs.

These beans are destined to be processed into meal (for animal feed) and edible oil by Carthage Grains, the only company capable of processing them.

Soybeans are unique in that they are both the seed and the final product. Are the seeds found in the fields of north-western Tunisia the result of a diversion of imported beans? Do they come from another import network?

In the recent history of GMOs, several countries have authorised their cultivation due to the massive presence of illegally introduced transgenic varieties, such as GM cotton in India and GM soybeans in Brazil5 . After years of illegal cultivation, Brazil has become the world’s second largest producer of GMOs. In Tunisia, the institutions remain silent: “We have proof of the presence of GMOs in our fields for several years, but the issue is very sensitive and we prefer to deal with it discreetly,” said a former official at the Gene Bank.

For his part, Leith Ben Becheur, farmer and former president of the Tunisian Farmers’ Union (SYNAGRI), is categorical: “Whether it is GMO or not, soybean cultivation is not suited to our climate, requires too much water and is not economically viable. It has no future in Tunisia“.

- “Quels sont les risques des OGM pour l’environnement ?” Inf’OGM. ↩︎

- Denis Meshaka, “Brésil : fin de partie pour un brevet soja OGM de Bayer ?”, Inf’OGM, 6 March 2023. ↩︎

- United Nations Environment Programme, “Capacity Building for the Implementation of the National Biosafety Framework.” ↩︎

- “Le Protocole de Cartagena sur les OGM”, Inf’OGM. ↩︎

- Eric Meunier and Christophe Noisette, “2002 – OGM : le calme avant la tempête”, Inf’OGM, 31 December 2002. ↩︎