News

Mon810 maize and teosinte: hybridisation still unmonitored

For several years, EFSA and ANSES have been asking Bayer to monitor the emergence of teosinte, the wild ancestor of maize, in fields cultivated with Mon810 maize in Portugal and Spain. In 2023, the company was still not doing so. However, the presence of teosinte in Europe has been confirmed. A scientific study has even shown experimentally that the Mon810 transgene can be transmitted from maize to teosinte plants collected in Spanish fields. The production of transgenic insecticidal protein is therefore not under control.

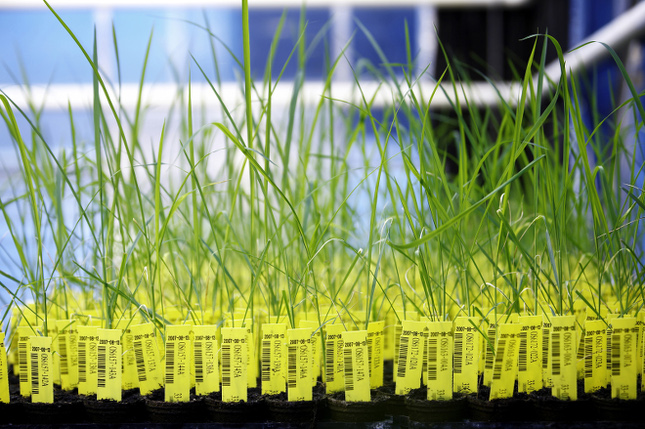

In 2023, Mon810 genetically modified maize, modified to express the Cry1Ab insecticide protein, was grown on 46,327 hectares in Spain and 1,898 hectares in Portugal. The cultivation of this maize was authorised in the European Union in 1998 for a period of ten years. Since then, it has remained legal due to a request for renewal of authorisation submitted by Bayer in 2007, to which the European Commission has not responded, a lack of response effectively amounting to an extension of the authorisation. Crops in Spain and Portugal are subject to annual environmental monitoring reports, which are reviewed each year by European and French expert committees. These reports reflect the experts’ concerns, repeated year after yeari, about the lack of adequate monitoring of this teosinte in Mon810 maize fields.

In Europe, teosinte can acquire the Mon810 maize transgene

The experts’ concerns were reinforced in 2024 by the publication of a Spanish scientific articleii. This article is in line with studies on the occurrence of crossbreeding between transgenic and non-transgenic maize initiated by Quist and Chapela in 2001, when they detected the presence of Bt transgenes in local Mexican maize varietiesiii.

In the 2024 article, as reported by ANSES in its opinion published in early 2025iv, Spanish scientists demonstrate “the production of the Cry1Ab protein and resistance to target insects in hybrid plants resulting from spontaneous crosses between MON810 maize and teosinte collected in Spain“. Indeed, after collecting teosinte plants in Spain and crossing them experimentally with MON810 maize over a three-year period, these scientists claim to have obtained crosses within a year that are capable of killing insects by producing Cry1Ab protein.

For the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA)v, these results “suggest that the potential for hybridisation between maize MON 810 and teosinte may be higher than previously assumed under experimental conditions“. They add that these teosinte/Mon810 maize hybrids can produce viable seeds and have a selective advantage over teosinte plants. However, they believe that further studies are needed ‘under real-life conditions’ to establish whether “the acquisition and expression of the cry1Ab gene in teosinte/maize hybrids could enhance their persistence or invasiveness“. As for whether this introduces an additional risk to target and non-target organisms of the transgenic Cry1Ab protein, the answer will depend on the results of a study to be conducted, if it is conducted…

It is indeed conceivable that if plants in nature start producing insecticide, the total amount of insecticidal protein will no longer be controlled (if it is controlled in GMO fields). Some areas would see insects exposed to quantities greater than the lethal dose to kill 50% of the exposed population (LD50), while other areas would see this quantity fall below the LD50. Such a situation could lead to the emergence of insects that have developed resistance to the insecticidal protein. In other words, insects resistant to Bt maize would be selected, which would deprive farmers of the use of natural Bt bacteria, authorised in organic farming, and encourage the proliferation of Bt teosinte in maize crops, at the risk of banning all “non-GMO” or organic maize cultivation. Breeders would be deprived of the use of teosinte to incorporate its hardiness traits into new non-GM varieties. Such contamination could also irreversibly disrupt the balance of biodiversity.

Experts remain critical of Bayer’s practices

The problem is that the concerns raised over several years about the presence of teosinte in Spain and, since this scientific article was published in 2024, the proven ability of these teosintes to acquire the Mon810 transgene, do not seem to have been heard by Bayer, which, in turn, is doing nothing about it.

ANSES points out, for example, that the company no longer surveys Portuguese farmers growing Mon810 maize, but only Spanish farmers. This is a practice that ANSES, like AESA, does not approve of, as it states that it would like the questionnaire developed by Bayer for farmers “to also be submitted to Portuguese farmers, since growing conditions, and therefore effects, may differ between Portugal and Spain“. As for the questions asked to Spanish farmers, these same experts explain that farmers “must indicate whether the five most abundant weeds in their MON810 maize fields are different from those identified in conventional maize crops“. This is an inadequate question, since it does not allow for the identification of teosinte if it is not one of the five most abundant weeds in Mon810 maize fields. ANSES and EFSA are therefore once again calling for “the presence of teosinte to be the subject of a specific and explicit question in the questionnaires sent to farmers“.

However, this information, which has not been collected by Bayer, forms the basis of the more specific monitoring work recommended by the experts. As the EFSA points out, “this lack of new data limits the ability to test specific risk hypotheses within the established pathways to harm, and to confirm or refute previously established assumptions in the ERA and risk management of maize MON 810“. For French and European experts, the presence of teosinte should be specifically taken into account in cases of MON810 maize cultivation because it can crossbreed with maize. This should translate into:

- monitoring for possible dispersion of the Cry1Ab transgene, a possible cross between maize and teosinte which, according to ANSES, could ultimately lead to “a flow of the transgene into conventional maize varieties“,

- – and monitoring for the appearance of “hybrid plants in refuge areas, which could compromise the effectiveness of a strategy to prevent the development of resistance to the Cry1Ab protein in insects“.

In summary, ANSES requests that “the presence of teosinte, and where applicable the surface area of these populations, as well as the presence of the cry1Ab transgene within these populations, be taken into account by the authorisation holder in its monitoring plan for MON810 maize“.

For its part, Bayer, as reported by ANSES and EFSA, considers that the appearance of teosinte is a general agronomic problem affecting all types of maize cultivation. Reading the ANSES, the company therefore concludes that “a report on the emergence or occurrence of teosinte in the context of the safety assessment of MON810 maize is not justified“.

Risks ahead?

The experts’ concerns relate to potential risks that are fairly easy to imagine in the event of transfer of the Mon810 transgene to teosinte present in Mon801 maize fields, especially if teosinte populations were to grow in these fields in the coming years.

One of the problems is that such a transfer could give teosinte plants insecticidal properties, as shown in a Spanish scientific article published in 2024. This situation would be all the more worrying given that these insecticide-producing teosinte plants could in turn spread and transmit the transgene to other non-transgenic maize plants. Ultimately, the production of transgenic protein would be amplified, as would, logically, the quantities of insecticidal protein present in the environment. In some places, it could be found in quantities greater than those anticipated when commercial cultivation was authorised in 1998. Non-target insects could then be impacted and killed by this protein. In other places, it could be found in insufficient quantities. In this case, target insects could have the opportunity to adapt and develop resistance.

The company’s reaction – or lack thereof – is surprising. While the European Union is seeing its teosinte population increase and researchers have shown that it is possible to transfer a transgene from GMO maize to these teosintes, the company has chosen to do nothing. This lack of response could allow a larger-scale agronomic problem to develop, providing an opportunity to promote new genetically modified plants as a solution…

i Eric Meunier, « Problems ahead due to cultivation of GMO maize in Europe? », Inf’OGM, 6 February 2024.

ii Arias-Martín M, Bonet MCE and Beldarraín IL, « Teosinte introduced into Spain and Bt maize: hybridisation rate, phenology and cry1ab toxin quantification in the hybrids », Revista de Ciências Agrárias, n°47, pp. 297-301, 2024.

iii David A. Cleveland et al., « Detecting (trans)gene flow to landraces in centers of crop origin: lessons from the case of maize in Mexico », Environ. Biosafety Res., n°4, pp.197–208, 2005.

iv Anses, « Note d’appui scientifique et technique (AST) de l’Agence nationale de sécurité sanitaire de l’alimentation, de l’environnement et du travail (Anses) relative à la demande de commentaires sur le rapport annuel (2023) de surveillance environnementale de la culture du maïs génétiquement modifié MON810 en Espagne et au Portugal », 8 January 2025.

v EFSA (European Food Safety Authority), Messéan, A., Álvarez, F., Devos, Y., Sánchez-Brunete, E., & Camargo, A. M., « Assessment of the 2023 post-market environmental monitoring report on the cultivation of genetically modified maize MON810 in the EU », EFSA Journal, 23(8), e9613, August 2025.